ECMI Minorities Blog. How Moscow ‘Eliminates’ Its National Minorities in the War with Ukraine

*** This entry is part of the special section of the ECMI Minorities Blog on National Minorities and the War in Ukraine. ***

Author: Ihor Lossovskyi | https://doi.org/10.53779/KGPE6877

* Ihor Lossovskyi, Ph.D., Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Minister of Ukraine of the First Class, is currently a Deputy Head of the State Service of Ukraine for Ethnic Policy and Freedom of Conscience. He occupied different diplomatic positions in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine (1993-2021) and was the Consul General of Ukraine in Toronto (2002-2006), Ambassador of Ukraine to Malaysia (2009-2010), and Ambassador-at-Large (2014-2016). He holds an M.Sc. degree from Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University (1979) and an MPA degree from Ukraine National Academy of Public Administration (2006). In 1989, he obtained a Ph.D. from the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Dr. Lossovskyi is the author of about 130 research articles and 3 monographs in the field of regional security and ethnic conflicts. Dr. Lossovskyi can be reached at the following address: i.lossovskiy@ukr.net

In a legal report, leading world experts have accused Russia of genocide in Ukraineand its intention to destroy the people of Ukraine, in violation of the UN Convention on Prevention and Punishment for the Crime of Genocide. This accusation is underpinned by a long list of evidence, including examples of mass murder, violence, inhuman treatment, and other indicators of genocide against Ukrainians.

In fact, Russia has also been accused by the international community of committing atrocities in Ukraine, with many national parliaments – including those of Canada, Czechia, Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the USA, and Ukraine referring to genocide in this context. In the middle of July 2022, the European Union and 43 nations issued a joint statement in support of Ukraine’s application to institute proceedings against the Russian Federation before the International Court of Justice under the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment for the Crime of Genocide.

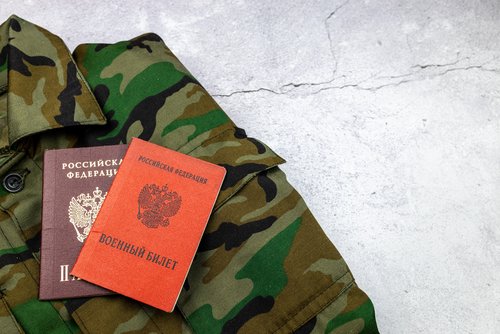

At the same time, Russia's aggressive war in Ukraine has revealed troubling tendencies in Russia itself, where we can see discriminatory attitudes to Russia’s own ethnic minorities who reside in the poorest areas of the country. We are specifically referring to the policy and results of the military draft during the intense phase of the Russo-Ukrainian war.

With Russia increasingly losing its military personnel in the war with Ukraine, the Kremlin is trying to make up for these terrible losses in every possible way, while the Russian government for a long time refrained from openly conducting a full-scale military mobilization. According to British military intelligence, as of the end of May 2022, the Russian army had lost a third of the ground forces that it had before the start of the hot phase of war in Ukraine. With an acute shortage of frontline military personnel, instead of a highly unpopular full-scale mobilization, Putin`s regime initially engaged in covert partial mobilization, particularly involving the male population from remote, economically-depressed regions with concentrated populations of national minorities, such as Russia’s Far East, North Caucasus, Buryatia, Khakassia, and Yakutia, as well as the occupied areas of Georgia, Ukrainian Donbas, and Crimea. Russia has also engaged Syrian mercenaries, prisoners jailed for criminal offenses, and representatives of private military companies (including the Wagner PMC) in the war in Ukraine.

Before the partial mobilisation launched in September, conscription was much less common in Russia's large economically and socially developed cities, where the majority of the population is ethnic Russian. One reason is that low-income representatives of national minorities were more willing to participate in the war as a way of making better money than they otherwise could in their economically-depressed regions, in contrast to the better circumstances of the inhabitants of big industrial centres with mostly ethnic Russian populations. A further apparent reason was the conscription policy, which effectively diluted the proportion of minorities within the general population. The number of representatives of the poorest national minorities from remote regions of Russia who were injured or killed during the war disproportionately exceeds the respective share of ethnic Russians who have suffered the same fate.

The opposition publication Mediazona (which was forced to leave Russia and work from abroad) published a report in mid-April 2022 analyzing the available data on the Russian military in Ukraine. Using open Russian sources (which, however, are far from complete), the journalists found 1,744 reports of Russian military casualties, which were much lower than the number of Russian casualties reported by Ukraine’s Ministry of Defence at that time (over 22,000). The figures provided by Mediazona are also significantly lower than the statistics provided by independent Western sources (about 17,000 Russians killed at that time). It is emphasized that most of those killed in action were military personnel from poor regions. Dagestan and Buryatia suffered the greatest losses, being among the poorest regions in Russia with national minorities of Buryats, Dagestanis, Tuvans, Khakass, and others. Meanwhile, there were almost no residents of Moscow and St. Petersburg (where 12% of Russia’s population reside) featured in the reports on soldiers killed in the war. According to a Mediazona more recent report, there were at least 5,801 confirmed Russian military deaths from 24 February to 24 August. Most of those killed in action came from the so-called ‘ethnic republics’, with Dagestan and Buryatia still leading the way. In Buryatia, the dead are buried almost every day.

Most reports about soldier deaths have been coming from the poorer regions: the average wage there is lower than the Russian median wage. Again, Moscow and St. Petersburg are almost never mentioned in those reports. By 18 May, according to Mediazona, Buryatia – second only to Dagestan in the number of Russian troops killed since the Russian invasion – had lost 117 soldiers, while Moscow, with a population about 15 times larger than Buryatia, had lost only three. As a percentage of the population, the incidence of death at war among the population of Buryatia was the highest in Russia. If we check the lists of Russian losses in this war, the prevalence of Muslim names is impressive, with soldiers primarily coming from units assembled in Dagestan and other republics of the North Caucasus. Citizens of Russia (or mercenaries) of Central Asian ethnicities, most of them Tajiks, are also dying disproportionately.

This was partly caused by poverty. For many young men in Buryatia, Tuva, or Dagestan, signing a contract with the military was one of the few options for a regular income and an attractive career. The Russian army is disproportionately composed of poor, ethnically non-Russian soldiers. But unlike in the US military, who recruit among minorities for voluntary military service, few representatives of Russian minorities have any illusions regarding their equality, both in the army and beyond. Russia is a country where the Slavic majority accounts for 80% of the population, with deep roots of ethnic Russian cultural dominance and racism which still remains the norm. European non-Slavic minorities in Russia, such as the Finno-Ugric Udmurt, Komi, and Erzya, also complain that their cultures and languages are oppressed or marginalized.

As Russia's losses in Ukraine increase day by day, such ethnic discrimination has become strikingly obvious. People in remote areas of Russia are increasingly concerned about the prospect of sending their sons and husbands to die in a war waged for the imperial idea of ‘Slavic unity.’ It is no coincidence that one of the most significant anti-war movements in Russia is not led by intimidated Moscow liberals, but rather the national movement ‘Buryats Against War’. In Buryatia and other peripheral minority regions of Russia, some local activists are trying to oppose the Kremlin's harsh censorship by creating anti-war posters in their native languages (Buryat, Kalmyk, Chuvash). Since the Russian state machine focuses on ethnic Russians, these slogans go almost unnoticed on the radars of federal censors, repressive authorities, and the police. Even liberal ethnic Russians do not believe – or do not want to believe – the high level of domestic racism and xenophobia that exists in Russia. Blinded by their racial privilege, most ethnic Russians (including the liberal intelligentsia, the opposition, and other educated people having to live in exile abroad) fail to realize the legacy of imperialism and colonialism that Russia weaponizes against its previously-conquered neighbouring peoples.

As of September 21, 2022 President Putin announced a ‘partial’ military mobilization for the war in Ukraine; that night, the president of the Free Buryatia Foundation stated that ‘Buryatia experienced one of the most terrible nights in its history’. The intensity of the recruitment drive in Buryatia has further fueled suspicions that ethnic minorities are being sent to fight and die in Ukraine at disproportionate rates. Analysis by activist groups and the media have raised suspicions that ethnic minorities are also dying at disproportionately high rates. By the beginning of September, troops from Dagestan, Buryatia, and Krasnodar in southern Russia had lost the most soldiers—over 200 deaths from each region. By comparison, only 15 people from the Moscow region, which accounts for almost one-tenth of Russia’s population, had been killed in battle. As former Mongolian President T. Elbegdorj stated on September 23: ‘Since the start of this bloody war, ethnic minorities who live in Russia suffered the most,’ he said. ‘The Buryat Mongols, Tuva Mongols, and Kalmyk Mongols have suffered a lot. They have been used as nothing more than cannon fodder.’

The 300-year imperial history of Russia, beginning with Peter I's proclamation of the Tsardom of Muscovy as the Russian Empire in 1721, was a history of expansion accompanied by mass repression, bloody wars, and the elimination of dozens of local peopleswho stood in the way of the militant empire. Today, modern Russia, as a descendant and successor of that empire and led by Vladimir Putin, is trying to continue the aggressive imperial policy of domination aimed at independent and sovereign Ukraine, the population of its occupied territories, as well as its minority peoples living in various regions of the empire. However, modern international law, democratic values, and the standards and rules which the world follows in the 21st century are fundamentally different from the values and norms of the past. That is why Russia’s imperial policy of aggression and destruction is now encountering strong collective resistance by Ukraine and all the democratic countries of the world.

***

This blog post was prepared by the author in their personal capacity. The views expressed in this blog post are the sole responsibility of the author concerned and do not reflect the view of the European Centre for Minority Issues.